ARCHITECTURAL MONUMENTS AND MANOR PARK

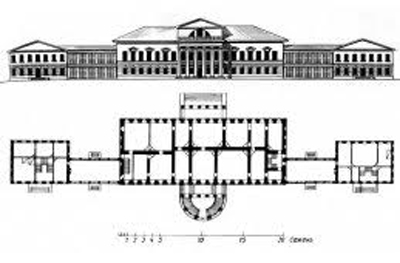

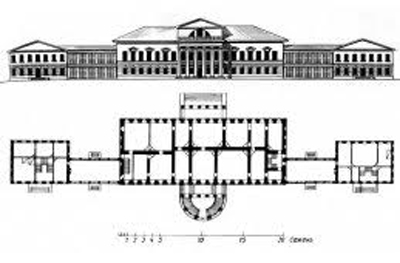

The largest building of the manor is the main house retaining the basis of the late XVIII century. During Ye. A. Volkonskaya time, Ionic porticoes and colonnades were added; they joined two new side wings with the central part. Upstairs, there was a mezzanine with Diocletian windows. Unfortunately, this rather harmonious appearance of the building did not survive. Subsequent reconstructions significantly distorted it. In 1843, the yard facing was added with a six-column semi-rotunda of the main entrance according to I. S. Kamensky’s project and the entire right wing was increased visually merging with the central part. After the revolution, the left gallery was dismantled terminating the connection of the main building with the southern wing. All of this eventually destroyed the symmetrical composition inherent in classicism. In 1920s, the palace was burnt and lost all the old interiors. Several ceremonial rooms were re-decorated in 1935-1938 clearly imitating the style of Russian classicism. The southern wing standing separately from the house lost its historic appearance during multiple reconstructions in 1810-ies.

The main house. Reconstruction as of the late XIX century

The main house. End of the XX century.

Southern wing of the main house. End of the XX century

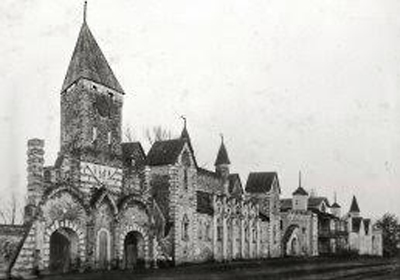

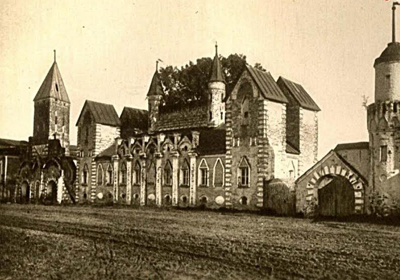

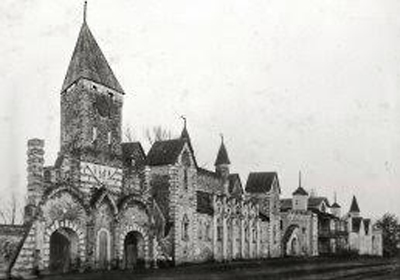

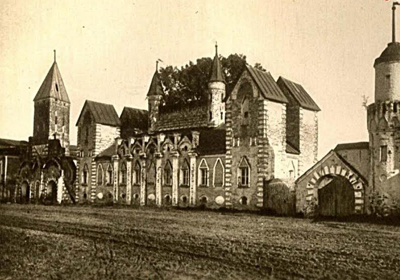

To the south of the palace, there is a whole street of outbuildings, which have appeared in 1810s. It included guest houses, manager’s office, clergy house and so on. Deliberate alternation of classicism and "medieval" houses of red brick with white details, sharp gables and turrets created illusion of an old European city street. This association was strengthened by towers with gates that stood between the buildings and were dismantled in 1930s. The romantic "small town" in Sukhanovo was one of the most interesting ensembles of this kind among Russian manors.

The "street" of outbuildings. Early XX century

The "street" of outbuildings. Late XX century

Many expressive art accents filled the space of the Sukhanovo manor park. To the north of the palace, near cascading ponds, there is a zone of "historical memories" including monuments to Alexander I (by V. P. Stasov) and Empress Elizaveta Alekseyevna.

The monument to Alexander I. Beginning of the XX century. Did not survive

The fence in the park. Early XX century. Did not survive

Nearby, there was an elegant aviary with a four-column semi-rotunda at the center. Together with the singing of birds, ancient forms of architecture were a symbol of eternal youth and beauty and reminded the prince of the years of his friendship with the deceased imperial couple. Nearby, on the lake shore, there was another memory of the irretrievably departed past - a statue of "The Girl with a Broken Jug", a replica of P. P. Sokolov’s sculpture in the Tsarskoselsky Park glorified by A. S. Pushkin. In Soviet times, the statue was moved to a new location closer to the mausoleum, where it lost the semantic link with water and its flow embodying the transience of time.

"The Girl with a Broken Jug" statue. End of the XX century

Aviary. Early XX century. Did not survive

Building in the park. Early XX century. Did not survive

To the west from the palace, on a hill above the lake, there is a white eight-column rotunda - the "Temple of Venus", gazebo built at the beginning of the XIX century. Once, there was a statue of the love goddess inside. Frieze reliefs allegorically tell about various "manor pleasures." From the rotunda – gazebo, a now non-existent pier with marble sphinxes was seen. This part of the park was used for relaxation and entertainment. The Sliding Hill was nearby; behind the lake, there was a farm. From the gazebo, through many times reconstructed bridge across the ravine, an alley is directed to the farthest corner of the park, where Volkonsky family temple-mausoleum of the metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky is located on the steep cliff. It was a space for personal family memories.

White eight-column rotunda – the "Temple of Venus" gazebo, end of the XX century.

Bridge across the ravine in the park, early XX century.

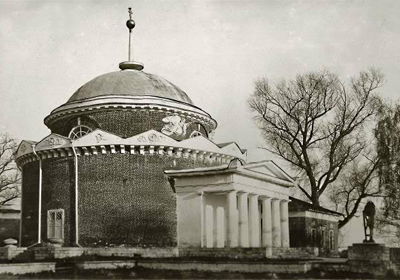

The metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky church-tomb is the most prominent architectural construction in the Sukhanovo manor. In February 1813, princess Ye. A. Volkonskaya petitioned about the intention to build a church with the burial place for her recently deceased husband D. P. Volkonsky. The construction was carried out within an extremely short period of time, the church was consecrated on September 21 of the same year. Except the temple-mausoleum – the metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky rotunda church consecrated in honor of the prince’s heavenly patron, the ensemble included two almshouse buildings on both sides and a semicircular gallery with a colonnade enveloping the mausoleum from behind. Directly behind the mausoleum, the colonnade was added with a bell tower with arched gate at the bottom.

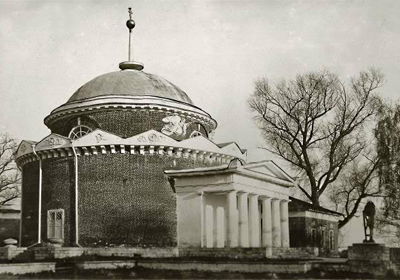

A view of the Volkonskys’ temple-mausoleum. Middle of the XIX century.

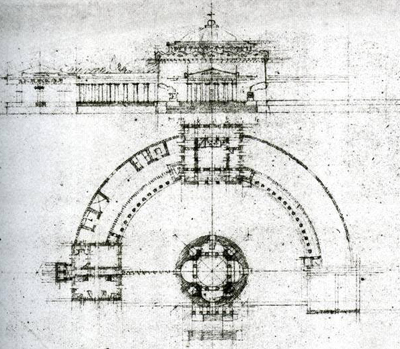

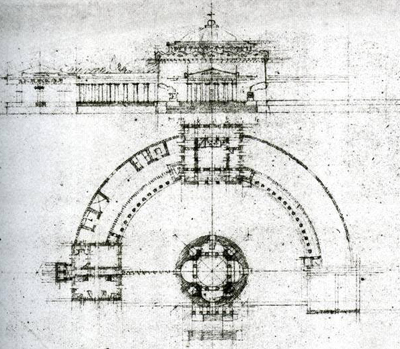

Since information about the project author could not be found for a long time, there were different assumptions about the authorship of such a stylish building by one of the Empire major architects. There was no doubt about the first row name. For some time, a popular version about the architect V. P. Stasov, who designed a monument to Alexander I for Sukhanovo by P. M. Volkonsky 's order, seemed to be quite convincing. However, the issue was finally resolved after the discovery of Domenico Gilardi’s drawings in Switzerland, which left no doubt about his authorship of the family tomb by the princess’ order. Thus, the Sukhanovo mausoleum became the first major independent work of the young architect, who had just returned from Milan to Moscow.

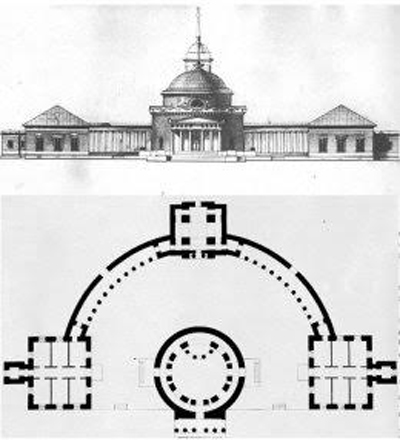

Volkonskys’ mausoleum project (one of the variants). By D. Gilardi. 1813.

Iconostasis project for the Volkonskys’ church-tomb. By D. Gilardi. 1813.

Iconostasis in the Volkonskys’ temple-mausoleum. Early XX century. Did not survive

Searching for the image, Gilardi was guided by Northern Italy urban cemetery complexes, many of which were built at the height of the Napoleonic Empire after the decree of 1804 prohibiting burials within the city walls. At the center of such ensembles, as a rule, there was a domed chapel visually reminiscent of the Roman Pantheon, and colonnades for burials went in different directions from it. In Sukhanovo, their purpose was purely decorative and the tomb was placed in a crypt under the church. Gilardi created a vivid image of a solitary sorrowful temple, the entrance to which was decorated with cast iron gloomy altars, and the Diocletian window was overshadowed by figures of sad angels. By the early XX century, in addition to D. P. Volkonsky and his wife who had built the mausoleum, four more members of the Volkonsky family were buried in it and by it.

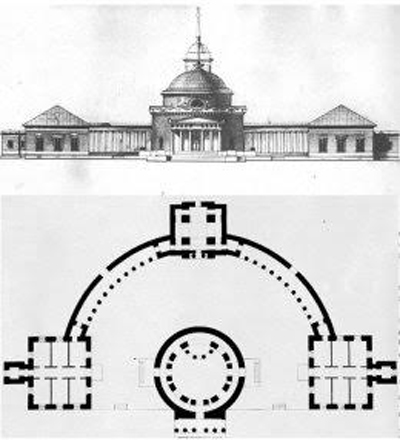

Reconstruction of the Volkonskys’ mausoleum original appearance. By B. L. Altshuller and M. M. Yermolayev

Cast iron altar at the entrance to the Volkonskys’ mausoleum. Early XX century.

Unfortunately, after a coup in 1917, this outstanding architectural monument of the Empire was savagely mutilated. First, it was looted losing the genuine Gilardi’s iconostasis and other decorations. In 1930s, during the sanatorium reconstruction, the colonnade and the bell tower were destroyed, the almshouses were overbuilt and connected to the central part by transitions. The altars and angel figures were destroyed, the walls were covered with stucco and yellow "state" painting. All Volkonskys’ graves were opened and they were reburied in a mass grave near the mausoleum.

The main house. Reconstruction as of the late XIX century

The main house. End of the XX century.

Southern wing of the main house. End of the XX century

To the south of the palace, there is a whole street of outbuildings, which have appeared in 1810s. It included guest houses, manager’s office, clergy house and so on. Deliberate alternation of classicism and "medieval" houses of red brick with white details, sharp gables and turrets created illusion of an old European city street. This association was strengthened by towers with gates that stood between the buildings and were dismantled in 1930s. The romantic "small town" in Sukhanovo was one of the most interesting ensembles of this kind among Russian manors.

The "street" of outbuildings. Early XX century

The "street" of outbuildings. Late XX century

Many expressive art accents filled the space of the Sukhanovo manor park. To the north of the palace, near cascading ponds, there is a zone of "historical memories" including monuments to Alexander I (by V. P. Stasov) and Empress Elizaveta Alekseyevna.

The monument to Alexander I. Beginning of the XX century. Did not survive

The fence in the park. Early XX century. Did not survive

Nearby, there was an elegant aviary with a four-column semi-rotunda at the center. Together with the singing of birds, ancient forms of architecture were a symbol of eternal youth and beauty and reminded the prince of the years of his friendship with the deceased imperial couple. Nearby, on the lake shore, there was another memory of the irretrievably departed past - a statue of "The Girl with a Broken Jug", a replica of P. P. Sokolov’s sculpture in the Tsarskoselsky Park glorified by A. S. Pushkin. In Soviet times, the statue was moved to a new location closer to the mausoleum, where it lost the semantic link with water and its flow embodying the transience of time.

"The Girl with a Broken Jug" statue. End of the XX century

Aviary. Early XX century. Did not survive

Building in the park. Early XX century. Did not survive

To the west from the palace, on a hill above the lake, there is a white eight-column rotunda - the "Temple of Venus", gazebo built at the beginning of the XIX century. Once, there was a statue of the love goddess inside. Frieze reliefs allegorically tell about various "manor pleasures." From the rotunda – gazebo, a now non-existent pier with marble sphinxes was seen. This part of the park was used for relaxation and entertainment. The Sliding Hill was nearby; behind the lake, there was a farm. From the gazebo, through many times reconstructed bridge across the ravine, an alley is directed to the farthest corner of the park, where Volkonsky family temple-mausoleum of the metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky is located on the steep cliff. It was a space for personal family memories.

White eight-column rotunda – the "Temple of Venus" gazebo, end of the XX century.

Bridge across the ravine in the park, early XX century.

The metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky church-tomb is the most prominent architectural construction in the Sukhanovo manor. In February 1813, princess Ye. A. Volkonskaya petitioned about the intention to build a church with the burial place for her recently deceased husband D. P. Volkonsky. The construction was carried out within an extremely short period of time, the church was consecrated on September 21 of the same year. Except the temple-mausoleum – the metropolitan Dimitry Rostovsky rotunda church consecrated in honor of the prince’s heavenly patron, the ensemble included two almshouse buildings on both sides and a semicircular gallery with a colonnade enveloping the mausoleum from behind. Directly behind the mausoleum, the colonnade was added with a bell tower with arched gate at the bottom.

A view of the Volkonskys’ temple-mausoleum. Middle of the XIX century.

Since information about the project author could not be found for a long time, there were different assumptions about the authorship of such a stylish building by one of the Empire major architects. There was no doubt about the first row name. For some time, a popular version about the architect V. P. Stasov, who designed a monument to Alexander I for Sukhanovo by P. M. Volkonsky 's order, seemed to be quite convincing. However, the issue was finally resolved after the discovery of Domenico Gilardi’s drawings in Switzerland, which left no doubt about his authorship of the family tomb by the princess’ order. Thus, the Sukhanovo mausoleum became the first major independent work of the young architect, who had just returned from Milan to Moscow.

Volkonskys’ mausoleum project (one of the variants). By D. Gilardi. 1813.

Iconostasis project for the Volkonskys’ church-tomb. By D. Gilardi. 1813.

Iconostasis in the Volkonskys’ temple-mausoleum. Early XX century. Did not survive

Searching for the image, Gilardi was guided by Northern Italy urban cemetery complexes, many of which were built at the height of the Napoleonic Empire after the decree of 1804 prohibiting burials within the city walls. At the center of such ensembles, as a rule, there was a domed chapel visually reminiscent of the Roman Pantheon, and colonnades for burials went in different directions from it. In Sukhanovo, their purpose was purely decorative and the tomb was placed in a crypt under the church. Gilardi created a vivid image of a solitary sorrowful temple, the entrance to which was decorated with cast iron gloomy altars, and the Diocletian window was overshadowed by figures of sad angels. By the early XX century, in addition to D. P. Volkonsky and his wife who had built the mausoleum, four more members of the Volkonsky family were buried in it and by it.

Reconstruction of the Volkonskys’ mausoleum original appearance. By B. L. Altshuller and M. M. Yermolayev

Cast iron altar at the entrance to the Volkonskys’ mausoleum. Early XX century.

Unfortunately, after a coup in 1917, this outstanding architectural monument of the Empire was savagely mutilated. First, it was looted losing the genuine Gilardi’s iconostasis and other decorations. In 1930s, during the sanatorium reconstruction, the colonnade and the bell tower were destroyed, the almshouses were overbuilt and connected to the central part by transitions. The altars and angel figures were destroyed, the walls were covered with stucco and yellow "state" painting. All Volkonskys’ graves were opened and they were reburied in a mass grave near the mausoleum.